The negative effects of website delay are well known. Faster is better (Shneiderman 1984, Bouch, Kurchinsky, and Bhatti 2000, Galletta et al. 2004). The trade-off between breadth and depth in menu design has been studied extensively. Wider is better (Jacko et al. 1995, Zaphiris and Mtei 1997, Larson and Czerwinski 1998). User familiarity with terminology and structure in website design has also been studied. Familiar is better (Edwards and Hardman 1989). However, the interaction between all three factors has not been studied until recently. Dennis Galletta, Raymond Henry, Scott McCoy, and Peter Polak analyzed how familiarity and breadth dampen the ill effects of website delay by increasing the “scent” of the target page (Galletta et al. 2006). This article summarizes their results.

The Cost of Information Foraging

Information foraging theory holds that humans alter their strategies and structure their environment to maximize their rate of gaining valuable information per unit cost, given the constraints of our environment (Pirolli and Card 1999). Costs include resource costs (calories, money, time, etc.) and opportunity costs (Hames 1992). or the benefits that could be gained by engaging in other activities. Constraints include the profitability of target information sources and the cost of accessing them. As we navigate hypertext structures, we are constantly reevaluating the cost of finding that next tasty morsel of information in an effort to optimize our intake of useful and valuable information (Katz and Byrne 2003).

Information Scent and Natural Selection

Attention! Supply Is Limited

Humans have a limited amount of attention (King 2003) yet the amount of information we have to consume continues to grow. We use informating foraging strategies to maximize amount of useful information we consume with our limited bandwidth.

Website structure is made up of links, site hierarchy, and the nodes that must be accessed to find information. At each node we make a decision, evaluating the cost and probability of reaching our target. Studies have shown that we prefer low-cost strategies that maximize our hit rates (Todd and Benbasat 1999). We use “information scent” to evaluate this path-following effort by using “proximal cues” like hypertext links and bibliographic citations. Paths with a strong “scent” give users a better idea where they are going (“distal” content) and the promise of speedy delivery (Chi et al. 2000). The theory goes that users will prefer sites offering low-cost information access in terms of time and cognitive effort over high-cost sites. Over time, with the process of natural selection, sites that are slow and difficult to navigate will either evolve to improve returns on information foraging, or be abandoned for lower cost alternatives.

“The basic hypothesis of Information Foraging Theory is that, when feasible, natural information systems evolve towards stable states that maximize gains of valuable information per unit cost.” (Pirolli and Card 1999)

The scent is made up of link text, images, layout, and other clues. If the scent of a site is too low, users tend to become lost in a random walk through hyperspace, and may jump to another “patch” of information. If the scent is strong enough, users can easily find their target information and will avoid the wrong paths. We look for these digital tea leaves (read “proximal cues”) in a site’s structure.

“Information scent is the (imperfect) perception of the value, cost, or access path of information sources obtained from proximal cues, such as bibliographic citations, WWW links, or icons representing the sources.” (Pirolli and Card 1999)

Users report “site size, unfamiliar material, predictability of link destinations, unfamiliar terminology, and hierarchical structure” as reasons for becoming lost. These reasons roughly fall into two dimensions, site depth and lack of familiarity, the two factors studied in this article along with website delay.

Caution: Low Scent Ahead

As the depth of a site increases, the cost of false alarms can quickly increase the number of pages viewed from linear to exponential (Pirolli 2003). When the average breadth multiplied by the false alarm factor is greater than one (b * f > 1) a critical threshold between linear and exponential search costs is crossed (Woodruff et al. 2001). So small changes in information scent can have a large effect on search costs.

Damping the Effects of Website Delay

Web site delay raises the cost of foraging for information by pushing the target further into the future, reducing the information scent. Deep and unfamiliar sites magnify the cost of delay as the disoriented user traverses up and down site levels looking for a stronger scent. Conversely the cost of slow sites can be mitigated by increasing site breadth and familiar terminology to minimize the number of clicks and cognitive cost necessary to reach the target.

Thus the authors submit that studying one of these factors in isolation does not provide a complete picture of the costs associated with browsing a site to find target information. Their study of 160 undergraduate business majors on two sample websites focused on the three-way interaction between these factors to predict user attitudes (feelings), performance (task completion), and behavioral intentions (to return and recommend the site to others). The goal was to find how familiarity and site breadth dampens the effects of website delay (see Figure 1).

Reprinted by permission, Dennis Galletta, When the Wait Isn’t So Bad: The Interacting

Effects of Website Delay, Familiarity, and Breadth, Information Systems Research,

volume 17, number 1, March, 2006. Copyright 2006, the Institute for

Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway

Drive, Suite 310, Hanover, MD 21076 USA.

Calculating the Cost of Familiarity and Breadth

Decreasing breadth and increasing depth will decrease the rate at which information is acquired while decreasing familiarity with the terminology used in links pointing to lower level pages will increase trial and error behavior. In a perfectly familiar site, the number of clicks to find the target information will equal the number of levels required to access that information. A perfectly unfamiliar site requires a brute force systematic search with backtracking, requiring many more clicks to find the destination. On average the goal information will be found halfway through the search, so the formula to predict the number of clicks required for a perfectly unfamiliar site is as follows:

“The expected number of clicks to reach the desired node is a function of the number of links per page and the number of levels.

“Where n = the number of links per page (assumed to be constant throughout) and L = the number of levels to traverse. Counting from the level under the home page, at each level i, there are ni intermediate pages.”

So for a 4-level site with 3 links on each page, a perfectly unfamiliar site would require 40 clicks, and a 2-level site with 9 links per page (both have 81 pages) would require 10 clicks. In reality the number of clicks is somewhat less for a deep site and somewhat more for a wide site (see Table 1), but the predicted trend holds true.

| Deep (4 levels to traverse with 3 links each) (total time sec.) | Broad (2 levels to traverse with 9 links each) (total time sec.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Familiar site | 6.5 clicks (predicted: 4) 52 sec. (predicted: 32) |

3.8 clicks (predicted: 2) 30.4 sec. (predicted: 16) |

| Unfamiliar site | 26.5 clicks (predicted: 40) 212 sec. (predicted: 320) |

8.2 clicks (predicted: 10) 65.6 sec. (predicted: 80) |

In theory, depth increases the number of clicks by a factor of 2 to 4, while unfamiliarity increases clicks by a factor of 5 to 10. In actual practice, the authors found that depth increases the number of clicks by a factor of 1.7 to 3.2 and unfamiliarity increases clicks by a factor of 2.2 to 4.1. Thus, perhaps due to the design of the experiment, unfamiliarity had a stronger influence on foraging costs than depth, but both factors are significant. Note that the difference in influence of these two factors may be smaller for sites with more depth and familiarity than those tested in the experiment.

For a worst case example, a uniform 8-second delay would impose a delay of 212 seconds on a brute force search in a deep, unfamiliar site of 4 levels with 3 links (see Table 1). Improving either breadth or familiarity has a dramatic effect on total delay. Moving to a familiar deep site the delay is reduced to 52 seconds, smaller by a factor of 4. Moving to a broad site the delay is reduced to 65.6 seconds. Add in familiarity and the total delay is reduced to 30.4 seconds, nearly 7 times smaller than the worst case delay. You can see that these factors interact with each other to increase or reduce the total cost of searching for information.

The Effects of Site Familiarity, Breadth, and Delay on Performance, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intentions

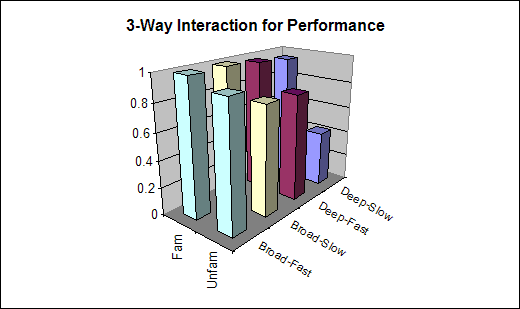

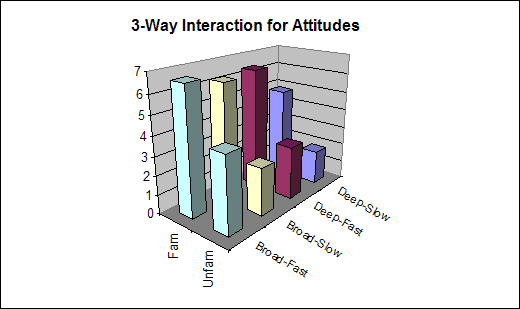

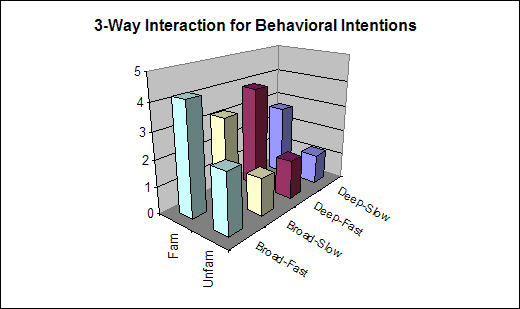

Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the three-way interaction of site breadth, familiarity, and delay on performance (Figure 3), attitudes (Figure 4), and behavioral intentions (Figure 5). The shortest bar in each chart represents the lowest performance (Figure 3), least positive attitudes (Figure 4), and lowest intentions to return and recommend (Figure 5). Figure 3 seems to show that both familiarity and breadth have a similar effect on performance while Figures 4 and 5 show that familiarity has a more significant effect on attitudes and behavioral intentions than does breadth. Indeed, under the conditions of the authors’ test, the effects of familiarity appear to be 2.8 times stronger than breadth on performance, while the effects of familiarity on attitudes is 12.1 times stronger than breadth. Note that the authors constructed worst case websites with ambiguous terms so these ratios would be closer in actual websites, but the trends would be similar. Clearly familiarity has a stronger effect on attitudes, performance, and behavioral intentions than the effects of breadth (over 4 times stronger). This study highlights the importance of proper information architecture, clearly labeled links, and clear menu terminology when designing web sites.

Reprinted by permission, Dennis Galletta, When the Wait Isn’t So Bad: The Interacting

Effects of Website Delay, Familiarity, and Breadth, Information Systems Research,

volume 17, number 1, March, 2006. Copyright 2006, the Institute for

Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway

Drive, Suite 310, Hanover, MD 21076 USA.

Reprinted by permission, Dennis Galletta, When the Wait Isn’t So Bad: The Interacting

Effects of Website Delay, Familiarity, and Breadth, Information Systems Research,

volume 17, number 1, March, 2006. Copyright 2006, the Institute for

Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway

Drive, Suite 310, Hanover, MD 21076 USA.

Figure 5, which was not included in the journal article, shows the three-way interaction of familiarity, breadth, and delay on behavioral intentions to return and recommend the site to others. Behavioral intentions are affected not unlike attitudes, with a more pronounced effect of speed on intentions to return, especially for a broad site.

Reprinted by permission, Dennis Galletta

We interviewed Dennis Galletta about his article:

WSO: What lessons should webmasters take away from your study?

Dennis Galletta: Sure, a slow site should be wide and familiar. But more importantly, any one or two of the three can help compensate for the other(s). For example, an unfamiliar site should be faster and wider. A deep site should be fast and familiar. Webmasters should make sure they can avoid the dreaded slow-unfamiliar-deep! Also, webmasters should work to make sure they have high information scent for users in all cases. They might conduct tests and track clicks and find where users are backtracking, indicating they are lost. They might also ask the users if they had any trouble finding the bottom nodes they were looking for.

WSO: What is more important, familiarity or breadth when you have a slow site?

Galletta: Our testing indicated that familiarity was more powerful than depth – going from 2 to 4 levels. Perhaps more levels would make it more like familiarity. Note that, in Table 1, unfamiliarity adds 5 to 10 times the number of clicks, while depth added 2 to 4 times the number of clicks. We would probably have to go down another 2 or 3 levels to make them similar in clicks, and therefore, perhaps similar in effect.

Conclusions

The three factors studied, breadth, familiarity, and website delay act in a synergistic way on attitudes, performance, and behavioral intentions. One or more of the factors can be changed to compensate for the negative effects of another. For example, if the scent is low because of slow pages, attitudes and performance can be improved by increasing breadth, or improving familiarity with the terminology used. Similarly if the scent is low due to unfamiliar terms and long delays, the site can be broadened. The authors conclude that rather than focusing on the impact of one of these factors on attitudes and performance, all three factors must be considered for a complete picture. The tests showed that familiarity had a more significant effect than breadth on performance, attitudes, and behavioral intentions, so web designers should choose navigation terminology with care.

Web developers should try to optimize all three factors to maximize the likelihood that users will return to their sites, browse their content, and recommend them to others. Page display times should be kept to a minimum, links should use familiar terminology, and breadth should be kept wide (7-9) with more links on intermediate pages. When one or more of these factors cannot be optimized, the others can be used to compensate. Conversely, if a site is expected to be highly familiar with few levels of hierarchy, graphics could be added to make the site more attractive.

Further Reading

- Bouch, A., Kuchinsky, A., and N. Bhatti (2000), “Quality is in the Eye of the Beholder: Meeting Users’ Requirements for Internet Quality of Service,”

- in Proceedings of CHI2000 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York: ACM Press, 2000), 297-304. Found that latency quality ratings drop-off at around 8 to 10 seconds.

- Chi, E. H., P. Pirolli, J. Pitkow (2000) “The scent of a site: A system

for analyzing and predicting information scent, usage,

and usability of a web site,” - Proc. SIGCHI, The Hague, The

Netherlands. Association for Computing Machinery, 161-168. - Dennis, A. R., and N.J. Taylor, “Information foraging on the web: The effects of ‘acceptable’

Internet delays on multi-page information search behavior.” - Found that acceptable delays of 7 seconds cause changes in search behavior in test subjects as predicted by information foraging theory. Acceptable delays caused more time examining particular pages, and fewer pages were examined. In other words delays caused more in-patch foraging and fewer visits to other patches. Decision Support Systems 42 (2006) 810-824.

- Edwards, D. M.,, and L. Hardman (1989) “‘Lost in hyperspace’ Cognitive

mapping and navigation in a hypertext environment,” - Ch. 7. R. McAleese, ed. Hypertext: Theory into Practice. Ablex

Publishing, NJ, 90-105. - Galletta, D., Henry, R., McCoy, S., and P. Polak (2004) “Web Site Delays: How Tolerant are Users?,”

- Found that “decreases in performance and behavioral intentions begin to flatten when the delays extend to 4 seconds or longer, and attitudes flatten

when the delays extend to 8 seconds or longer.” Journal of the Association for Information Systems 5 no. 1, 1-28. - Galletta D,, Henry, R., McCoy, S., & P. Polak (2006), “When the Wait Isn’t So Bad: The Interacting Effects of Website Delay, Familiarity, and Breadth,â€

- Information Systems Research, (17):1, March, 2006. Examined whether website delay, breadth, and familiarity have interactive effects on user psychology and performance. A significant three-way interaction among all three factors showed that the ill effects of delay can be dampened by familiarity and breadth. Developers are urged to consider site familiarity, breadth, and delay together rather than separately.

- Harnes, R. (1992) “Time allocation,”

- In E. A. Smith & B. Winterhalder (Eds.), Evolutionary ecology and human behavior (pp. 203-235). New York: de

Gruyter. - Jacko, J. A., G. Salvendy, and R. J. Koubek (1995) “Modeling of menu

design in computerized work,” - Interacting Comput. 7(3) 304-330.

- Katz, M. A., and M. D. Byrne (2003) “The effect of scent and breadth

on use of site-specific search on e-commerce web sites,” - ACM

Trans. Human-Comput. Interaction 10(3) 198-220. - King, A. (2003), “Flow in Web Design: Attention! Supply Is Limited,”

- Found that humans have a processing power of around 5,400 to 7,560 bits of information per minute. Speed Up Your Site: Web Site Optimization,, Chap. 2, New Riders Press, 2003, p. 30.

- Larson, K., and M. Czerwinski (1998), “Web page design: Implications

of memory, structure and scent for information retrieval,” - Proc.

SIGCHI, Los Angeles, CA. Association for Computing Machinery,

25-31. - Morris, M. G., and J. M. Turner (2001), “Assessing Users’ Subjective Quality of Experience with the World Wide Web: An Exploratory Examination of Temporal Changes in Technology Acceptance,”

- International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 54 (2001): 877-901. Found that the speed at which your pages display affects perceived quality of service. For non-incremental displays pages that displayed in over 11 seconds were perceived to be of low quality.

- Nielsen, J., (2004), “Deceivingly Strong Information Scent Costs Sales,”

- Users will often overlook the actual location of information or products if another website area seems like the perfect place to look. Cross-references and clear labels alleviate this problem. Alertbox, Useit.com, August 2004.

- Pirolli, P. (2003), “The Effects of Information Scent,”

- ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 10 (1) March 2003.

- Pirolli, P. (2007), Information Foraging Theory: Adaptive Interaction with Information

- From the inventor of information foraging and information scent comes this in-depth book about how and why users navigate the Web for information. A must read for web designers and developers. Oxford University Press, USA (2007).

- Pirolli, P., and S.K. Card, (1999) “Information foraging”

- The definitive work on information foraging theory. Psychological Review 106 (4) (1999) 643-675.

- Raybourn, T. (2002), “Cognitive Models for Web Design: Information Foraging Theory Applied,”

- Shows how information foraging theory can be used to improve web design. Pixelcharmer.com, May 2002.

- Shneiderman, B. (1984), “Response Time and Display Rate in Human Performance with Computers,”

- Computing Surveys 16, no. 3, 265-285. Keep it under 1-2 seconds, please.

- Todd, P., I. Benbasat (1999), “Evaluating the impact of DSS, cognitive

effort, and incentives on strategy selection,” - Inform. Systems Res. 10(4) 356-374.

- Woodruff, A., Faulring, A., Rosenholtz, R., Morrison, J., and Pirolli, P. (2001), “Using thumbnails

to search the Web,” - In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

CHI 2001 (Seattle). - Zaphiris, P., and L. Mtei (1997), “Depth vs. breadth in the arrangement

of Web links,” - University of Maryland, College Park, MD. http://www. otal.umd.edu/SHORE/.